Review of Kazmier Maslanka's Mathematical Visual Poem; "Newton's Third Law In Karmic Warfare"

BY Agniezska Iwanowski

Art Review: Kazmier Maslanka’s "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare"

By Agniezska Iwanowski

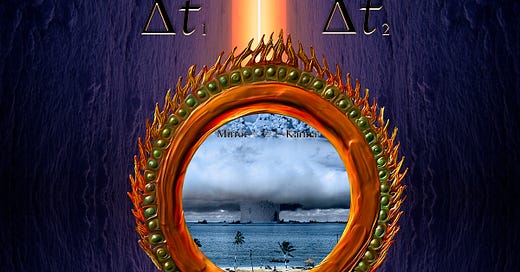

Kazmier Maslanka’s "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare" is a striking mathematical visual poem that transcends traditional artistic boundaries, weaving together science, spirituality, and poetics into a profound aesthetic experience. This work, illuminated in The STEAM Journal in 2016, exemplifies Maslanka’s innovative "Paradigm Poem" technique, where applied mathematical equations serve as vessels for poetic metaphor. The piece features a Joseon Dynasty Karma Mirror, an image of the nuclear explosion at Bikini Atoll, and a hellish planetary landscape, all framed by a mirrored sunrise and Newton’s Third Law of Motion. Through this composition, Maslanka explores the karmic repercussions of human actions, particularly the creation of nuclear weapons, while engaging deeply with conceptual metaphor, modern and postmodern art theories, and the legacies of artists like René Magritte and Guillaume Apollinaire. Additionally, the work resonates with Joseph Campbell’s mythological insights and Buddhist spiritual traditions, making it a rich tapestry of interdisciplinary dialogue.

Engagement with George Lakoff’s Theory of Conceptual Metaphor

Maslanka’s work functions as a vivid illustration of George Lakoff’s Theory of Conceptual Metaphor, which posits that metaphors are not merely linguistic devices but fundamental mechanisms of thought, mapping one conceptual domain onto another to facilitate understanding of abstract concepts. In "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare," Maslanka employs the "Paradigm Poem" technique to map the concrete source domain of physics (Newton’s Third Law) onto the abstract target domain of karmic spirituality. As Lakoff and his collaborator Mark Turner argue in “More Than Cool Reason; A Field Guide To Poetic Metaphor” (1989), metaphors like these allow us to reason about abstract domains (e.g., karma) using the inferential structure of more concrete domains (e.g., physics).

The mappings in Maslanka’s poem are meticulously detailed: mass (m1) is metaphorically transformed into “The Level of My Self-Righteousness,” suggesting that ego, like mass, has inertia and weight in social interactions. And on the other side of the equation (m2) “The Level of Your Self-Righteousness,” Consequentially, the change in velocity (Δv1) becomes “Me Taking Life from You” (or on the other side of the equation) (Δv2) “You Taking Life From Me,” framing the act of harming another as a form of acceleration toward death. Finally, the change in time (Δt1) is mapped onto “The Time It Takes For Me kill You” or on the other side of the equation (Δt2) “The Time It Takes For You To Kill You Me,” grounding the abstract concept of time in the visceral reality of mortality. These mappings align with Lakoff’s Event Structure Metaphor, where causes are forces, actions are movements, and difficulties are impediments. Here, the force of self-righteousness propels the action of taking life, with karmic consequences acting as an equal and opposite reaction.

The visual elements further enhance these metaphorical mappings. The Karma Mirror, reflecting the nuclear explosion, embodies the metaphor “KARMA IS EQUIVALENCE,” mirroring the conservation of momentum in Newton’s law. The hellish planet beneath the mirror aligns with the metaphor “KARMA IS HELL,” suggesting that actions (particularly destructive ones like nuclear proliferation) lead to a state of moral reckoning. Through these mappings, Maslanka uses Lakoff’s framework to explore the symmetry between physical laws and spiritual principles, making the abstract concept of karma tangible through the concrete structure of physics.

Lakoff’s Invariance Principle, which states that metaphorical mappings preserve the image-schematic structure of the source domain, is evident here. The structure of Newton’s Third Law—two forces in opposition yet equal—maps onto the karmic idea of reciprocal consequences, preserving the balance and symmetry inherent in both domains. This mapping allows viewers to reason about the abstract notion of karma using the concrete logic of physics, a hallmark of Lakoff’s theory that abstract concepts are understood through more tangible domains.

Relationship to Modern Art Theory

Within the context of modern art theory, Maslanka’s work aligns with the movement’s emphasis on breaking from traditional representation to explore new forms of expression, often through intellectual and conceptual frameworks. Modernism, flourishing in the early 20th century, sought to reflect the complexities of the modern world through abstraction, symbolism, and the integration of science and technology into art. Maslanka’s use of a mathematical equation as a poetic structure echoes the modernist fascination with science as a lens for understanding reality, akin to how artists like Wassily Kandinsky used geometric forms to express spiritual truths in works like Composition VIII (1923). Kandinsky’s abstraction aimed to evoke emotional and spiritual resonance through non-representational forms, much as Maslanka’s equation serves as a symbolic framework to explore karmic dynamics.

Another modernist parallel is found in Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a readymade that challenged the definition of art by presenting a urinal as an aesthetic object. Similarly, Maslanka repurposes Newton’s Third Law—a scientific artifact—as an artistic vessel, questioning the boundaries between science and poetry. The inclusion of the Bikini Atoll nuclear explosion within the Karma Mirror further resonates with modernism’s engagement with contemporary issues, such as the existential threats posed by technology and war. This mirrors the way Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) addressed the horrors of the Spanish Civil War, using distorted forms to convey the emotional and moral weight of violence. Maslanka’s work, with its hellish planet and nuclear imagery, similarly critiques the karmic consequences of humanity’s technological hubris, fitting squarely within modernism’s tradition of social commentary through innovative forms.

Relationship to Postmodern Art Theory

Postmodern art theory, emerging in the late 20th century, often embraces intertextuality, hybridity, and the deconstruction of grand narratives, favoring fragmented, pluralistic meanings over singular truths. Maslanka’s "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare" embodies these principles through its layered composition and blending of disparate elements—mathematics, spirituality, mythology, and historical imagery. The work’s intertextuality is evident in its appropriation of Newton’s equation, a Korean Joseon Dynasty Karma Mirror, and a U.S. government photo of the Bikini Atoll explosion, creating a dialogue across cultures, disciplines, and time periods. This mirrors the postmodern practice of artists like Cindy Sherman, who in her Untitled Film Stills (1977–1980) appropriates cinematic tropes to explore identity and representation, blending high and low culture to challenge fixed meanings.

The piece also reflects postmodernism’s deconstruction of binary oppositions, such as science versus spirituality or East versus West. By mapping a Western scientific equation onto an Eastern spiritual concept, Maslanka collapses these dichotomies, suggesting a unified framework where karma and physics coexist. This resonates with Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog (1994–2000), which juxtaposes the playful form of a balloon animal with the permanence of stainless steel, blurring the lines between kitsch and high art. Maslanka’s hellish planet and mirrored sunrise further enhance this postmodern fragmentation, presenting a surreal, disjointed landscape that defies a singular narrative, instead inviting viewers to construct their own interpretations of karmic warfare in the nuclear age.

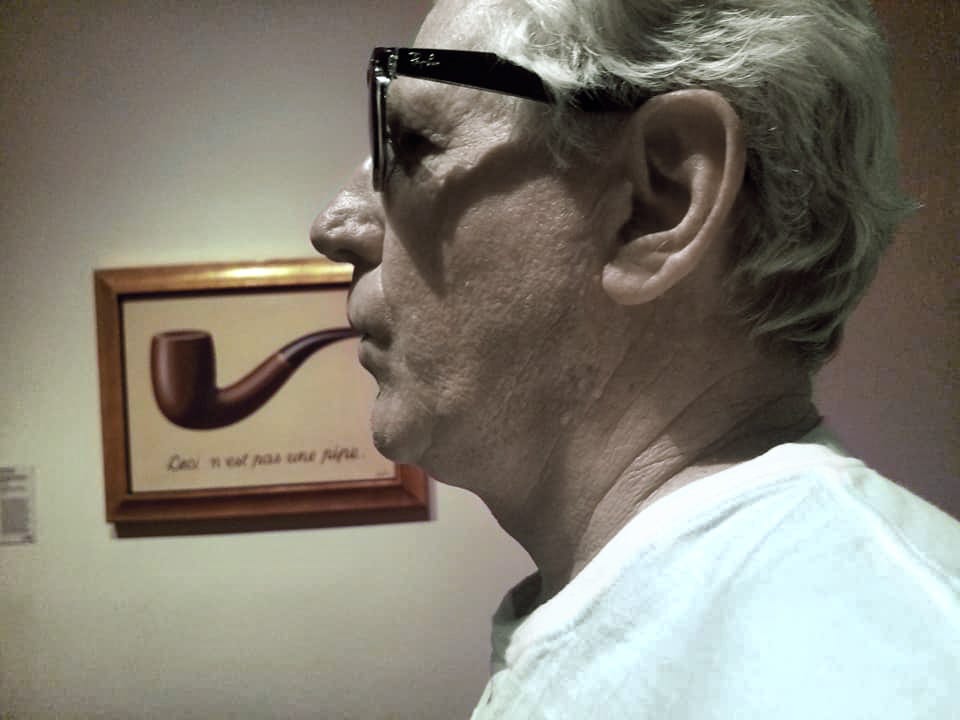

Doug Pinkston poses with “The Treachery of Images” by Rene Magritte

photo by Kaz Maslanka at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Relationship with René Magritte and Guillaume Apollinaire

Maslanka’s work shares a conceptual kinship with René Magritte, the Belgian surrealist known for challenging perceptions of reality through visual paradoxes. In Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (1929), a painting of a pipe is accompanied by the caption "Ceci n’est pas une pipe" ("This is not a pipe"), highlighting the distinction between representation and reality. Similarly, Maslanka’s "Karma = '=' = Mirror" equation within the Karma Mirror questions the nature of equivalence and reflection, suggesting that the mirror (a representation of image), the equal sign (a representation of value), and karma (a representation of action) are interconnected yet distinct. Both artists use their mediums to provoke philosophical inquiry, with Maslanka extending this surrealist tradition into the realm of mathematical poetry.

Guillaume Apollinaire, a pioneer of modernist poetry and a creator of calligrams, also finds a profound echo in Maslanka’s work, particularly through their shared belief in the transformative power of the imagination to expand reality. Apollinaire’s calligrams, such as Il Pleut (1918), where words are arranged to form the shape of falling rain, merge visual art and poetry to create a multisensory experience. Maslanka’s integration of Newton’s equation with poetic text and visual elements like the Karma Mirror and nuclear explosion similarly blurs the lines between text, image, and meaning, creating a layered, interdisciplinary artwork. Both artists experiment with form to enhance content—Apollinaire through typographic innovation, and Maslanka through mathematical structure—inviting viewers to engage with their works on multiple levels, from intellectual to emotional.

Apollinaire’s influence on Maslanka extends beyond form into a shared philosophical optimism and a rejection of the melancholic introspection that characterized 19th-century poetry. In Les Mamelles de Tirésias (1917), Apollinaire critiques the "pessimism more than a century old, ancient enough for such a boring thing," advocating for a modern mindset that embraces creativity, laughter, and the potential for enchantment in the face of adversity. This resonates deeply with Maslanka’s thematic concerns in "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare," where the hellish consequences of nuclear proliferation are met not with despair but with a reflective, karmic mirror that suggests a cycle of action and reaction—implying the possibility of change and accountability. Apollinaire’s belief, as noted in the book “Surrealism Road To The Absolute” by Anna Balakian, states that "the domain of the imagination is reality," aligns with Maslanka’s use of a scientific equation to explore spiritual concepts, expanding the viewer’s perception of reality through metaphor and imagination, much as Apollinaire sought to do for the surrealists who followed him.

Furthermore, Apollinaire’s role as a herald of a "new age of enchantment," as described in the document, mirrors Maslanka’s own prophetic stance. Apollinaire’s optimism about the future of art, his desire to "give man confidence in himself," and his vision of a world beyond mechanization and war find a parallel in Maslanka’s critique of nuclear technology through a karmic lens. While Apollinaire looked beyond "the grimness of mechanization" to a future of "enchanters," Maslanka uses the Bikini Atoll explosion to warn of technological hubris, yet frames it within a karmic cycle that suggests a potential for balance and redemption. Apollinaire’s influence on the surrealists, particularly André Breton, who saw him as "the last poet" incarnating the role with vitality and enthusiasm, underscores his legacy as a source of inspiration—a legacy Maslanka taps into by blending poetry, science, and spirituality in a way that challenges conventional boundaries, much as Apollinaire did with his own innovative forms and ideas.

Relationship with Joseph Campbell

Joseph Campbell’s influence on Kazmier Maslanka’s "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare" is profound, particularly in the mythological and spiritual dimensions that underpin the artwork’s exploration of karmic consequences in the nuclear age. Campbell, a 20th-century mythologist renowned for his work on comparative religion /mythology, argued that myths are not merely ancient stories but living metaphors that point to transcendent truths about the human experience. In his seminal work The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), Campbell describes myths as “the world’s dreams,” symbolic narratives that help individuals and societies navigate existential challenges by mapping the inner journey of the psyche onto external actions. Maslanka’s piece resonates with this perspective by using the Joseon Dynasty Karma Mirror, the Bikini Atoll nuclear explosion, and a hellish planetary landscape to create a modern myth—a narrative that reflects humanity’s collective confrontation with the consequences of its technological hubris.

Campbell’s concept of conflation, where spiritual ideas are mapped onto concrete forms, is evident in Maslanka’s mapping of karma onto Newton’s Third Law. Campbell often emphasized that metaphors in mythology point to realities beyond literal categories, as seen in his statement, “The word 'God' properly refers to what transcends all thinking.” In Maslanka’s work, the Karma Mirror—a mythological symbol from Korean Buddhist tradition—serves as a concrete form that reflects the abstract concept of nuclear karma, bridging the infinite cycles of cause and effect with the tangible reality of humanity’s actions. The Bikini Atoll explosion, a historical event, becomes a mythic symbol of destruction, akin to the apocalyptic imagery found in myths across cultures, such as the Norse Ragnarök or the Hindu Kali Yuga. By framing this event within the Karma Mirror, Maslanka aligns with Campbell’s view that myths use symbols to address universal human concerns, here focusing on the moral and spiritual fallout of the atomic age.

The hellish planet and the descent into a realm of judgment depicted in the artwork further resonate with Campbell’s analysis of the hero’s journey, a narrative structure he identified as universal across mythologies. In this framework, the hero often descends into an underworld—a place of trial and transformation—to confront their actions or inner demons before emerging with newfound wisdom. In Maslanka’s piece, humanity itself is the hero, facing the karmic mirror of its nuclear actions in a hellish landscape that evokes the underworlds of myth, such as the Greek Hades or the Buddhist Bardo State. The nuclear explosion at Bikini Atoll, with its fiery, destructive power, mirrors the trials Campbell describes, where the hero must face the consequences of their choices. For Campbell, this descent is not merely punitive but transformative, offering the potential for renewal. Maslanka’s mirrored sunrise, juxtaposed against the hellish planet, suggests a similar possibility of transformation—a dawning of awareness where humanity might awaken to the karmic implications of its actions and seek a path toward balance and peace.

Campbell also believed that myths and art play a critical role in addressing the crises of their time, a perspective that deeply informs Maslanka’s work. In The Power of Myth (1988), Campbell discusses the need for new myths to address the challenges of the modern world, particularly the existential threats posed by technology and war. He states, “The only myth that is going to be worth thinking about in the immediate future is one that is talking about the planet… and everybody on it.” The nuclear age, with its potential for global annihilation, represents precisely the kind of crisis Campbell believed required a mythic response. Maslanka’s "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare" answers this call by creating a visual poem that functions as a modern myth, using the language of science (Newton’s equation), spirituality (the Karma Mirror), and art (the hellish landscape and mirrored sunrise) to address the karmic consequences of nuclear proliferation. The Bikini Atoll explosion, a real event from 1946, is elevated to a mythic level, symbolizing humanity’s overreach and the urgent need for a collective awakening to the interconnectedness of all life—a theme Campbell often emphasized in his discussions of global consciousness.

Furthermore, Campbell’s exploration of Eastern mythologies, including Buddhism, enhances the connection to Maslanka’s work. Campbell frequently drew on Buddhist concepts like karma and interdependence in his analyses, noting their universal relevance. In Myths to Live By (1972), he writes, “The idea of karma is that your present experience is the result of your past actions, and your future will be the result of what you are doing now.” This cyclical understanding of action and consequence directly parallels Maslanka’s use of Newton’s Third Law to frame karmic warfare, where the creation of nuclear weapons generates a reciprocal reaction of suffering and destruction. Campbell’s appreciation for the Buddhist view of life as a web of interconnected actions aligns with Maslanka’s depiction of nuclear karma as a global phenomenon, affecting not just the perpetrators but the entire planet, as seen in the environmental devastation of Bikini Atoll and the hellish planet in the artwork.

Campbell also saw art as a vehicle for mythic renewal, a means of reawakening individuals to their role within the larger cosmic order. He often cited the artist’s role in creating “new symbols” that could guide humanity through periods of transition. Maslanka’s integration of a mathematical equation with poetic and spiritual elements exemplifies this role, offering a new symbolic language to grapple with the nuclear age. The Karma Mirror, as a reflective tool, invites viewers to engage in what Campbell called “the inner journey”—a process of self-examination and transformation. By confronting the image of the nuclear explosion within the mirror, humanity is called to recognize its own agency in creating this crisis and to seek a path toward healing, much as Campbell believed myths guide individuals toward wholeness.

In this light, Maslanka’s work can be seen as a mythic narrative in the Campbellian sense, one that uses the power of metaphor to address the spiritual and ethical dilemmas of the modern world. The artwork’s blend of science, spirituality, and art mirrors Campbell’s own interdisciplinary approach to mythology, which drew on diverse traditions to uncover universal truths. Through the lens of Campbell’s thought, "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare" emerges as a call to action—a modern myth that urges humanity to confront its nuclear karma, descend into the underworld of its own making, and emerge with the wisdom to create a more balanced and compassionate future.

The Karma Mirror in Buddhist Religion

In Buddhist tradition, particularly within Korean Seon (Zen) practices that inspire Maslanka, the Karma Mirror symbolizes a moment of reckoning after death. According to some East Asian mythologies, the deceased encounter demons in a hellish realm who present a mirror reflecting their accumulated karma. If the karma is negative, a price must be paid, often through suffering or rebirth into a lower realm. The Karma Mirror in Maslanka’s work, adorned with the Bikini Atoll explosion, serves this function by reflecting humanity’s "nuclear karma," suggesting that the creation of such destructive technology has karmic consequences that must be confronted. This aligns with Buddhist teachings on cause and effect, where actions (karma) shape future experiences, a principle Maslanka maps onto Newton’s Third Law to emphasize the inevitability of reciprocal consequences.

Conclusion

Kazmier Maslanka’s "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare" stands as a profound testament to the power of art to bridge disparate domains—science, spirituality, mythology, and history—into a unified meditation on humanity’s moral and existential challenges. Through the lens of George Lakoff’s theory of conceptual metaphor, Maslanka maps the physics of action and reaction onto the spiritual dynamics of karma, creating a framework that invites viewers to reason about abstract ethical dilemmas through the concrete logic of science. This interdisciplinary approach aligns with the legacies of modern and postmodern art, drawing on the intellectual rigor of modernism to critique nuclear proliferation while embracing postmodernism’s intertextual and hybrid nature to weave together diverse cultural and historical references.

The work’s engagement with René Magritte and Guillaume Apollinaire underscores its surrealist and experimental roots, with Apollinaire’s optimistic vision of art as a transformative force resonating deeply with Maslanka’s reflective critique of humanity’s technological hubris. Apollinaire’s belief in the imagination’s power to expand reality, as well as his rejection of 19th-century pessimism in favor of a modern, enchanted mindset, finds a parallel in Maslanka’s use of the Karma Mirror to confront nuclear karma while suggesting a path toward awakening, symbolized by the mirrored sunrise. This optimism, tempered by a clear-eyed acknowledgment of humanity’s destructive potential, positions Maslanka as a modern heir to Apollinaire’s legacy of poetic innovation and hope.

Joseph Campbell’s mythological framework further enriches the artwork, casting it as a modern myth that addresses the nuclear age’s existential crises. Campbell’s concepts of the hero’s journey, the power of myth to guide humanity through trials, and the need for new symbols to navigate global challenges illuminate Maslanka’s depiction of humanity’s descent into a hellish landscape of its own making. The Bikini Atoll explosion, framed within the Karma Mirror, becomes a mythic symbol of overreach, while the mirrored sunrise offers a Campbellian vision of transformation—a potential emergence from the underworld with newfound wisdom. Campbell’s emphasis on art as a vehicle for mythic renewal underscores the significance of Maslanka’s work as a call to awaken to the interconnectedness of all life, a theme that resonates with both Buddhist principles and Campbell’s global consciousness.

The intersection of Buddhism and the atomic bomb in Maslanka’s artwork adds a critical ethical dimension, grounding the piece in the historical reality of nuclear devastation while offering a spiritual lens for reflection. The Karma Mirror, rooted in Buddhist tradition, reflects the karmic consequences of the atomic bomb, from the immediate suffering of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the long-term environmental and human toll of tests like Bikini Atoll. By invoking Buddhist concepts of interdependence, impermanence, and the potential for enlightenment, Maslanka aligns with historical Buddhist responses to nuclear technology, such as Nichidatsu Fujii’s advocacy for peace, while urging viewers to consider the moral weight of humanity’s actions. The hellish planet and nuclear imagery serve as a stark reminder of the impermanence of the world, while the mirrored sunrise suggests a path toward compassion and wisdom—a Buddhist vision of transforming suffering into awakening.

Ultimately, "Newton's Third Law in Karmic Warfare" is a poignant and thought-provoking contribution to contemporary art, one that transcends traditional boundaries to address the pressing issues of our time. Maslanka invites viewers to confront the karmic weight of nuclear technology through a multifaceted lens—scientific, poetic, mythological, and spiritual—challenging us to reflect on our role in shaping the future. In doing so, the artwork not only critiques the past but also offers a hopeful vision for transformation, echoing Apollinaire’s belief in art’s capacity to enchant, Campbell’s call for new myths to guide humanity, and Buddhism’s emphasis on ethical action and interconnectedness. As a modern myth for the nuclear age, Maslanka’s piece stands as both a warning and an invitation: to face the mirror of our actions, to acknowledge the consequences of our choices, and to seek a more balanced and compassionate path forward.