Review: The Geometry of Enlightenment—Kazmier Maslanka’s Beginner’s Mind

By Alberto Indiana

In Zen, there is a well-known parable: A young monk, eager to prove his wisdom, visits an old master. He brags about his knowledge, his acts of compassion, his accomplishments. The master, silent, begins pouring tea. The cup fills, then overflows—spilling onto the table, onto the young monk’s lap. Startled, the monk protests. The old master replies, “I cannot help you, for your mind is like this cup—already full. You must always have Beginner’s Mind.”

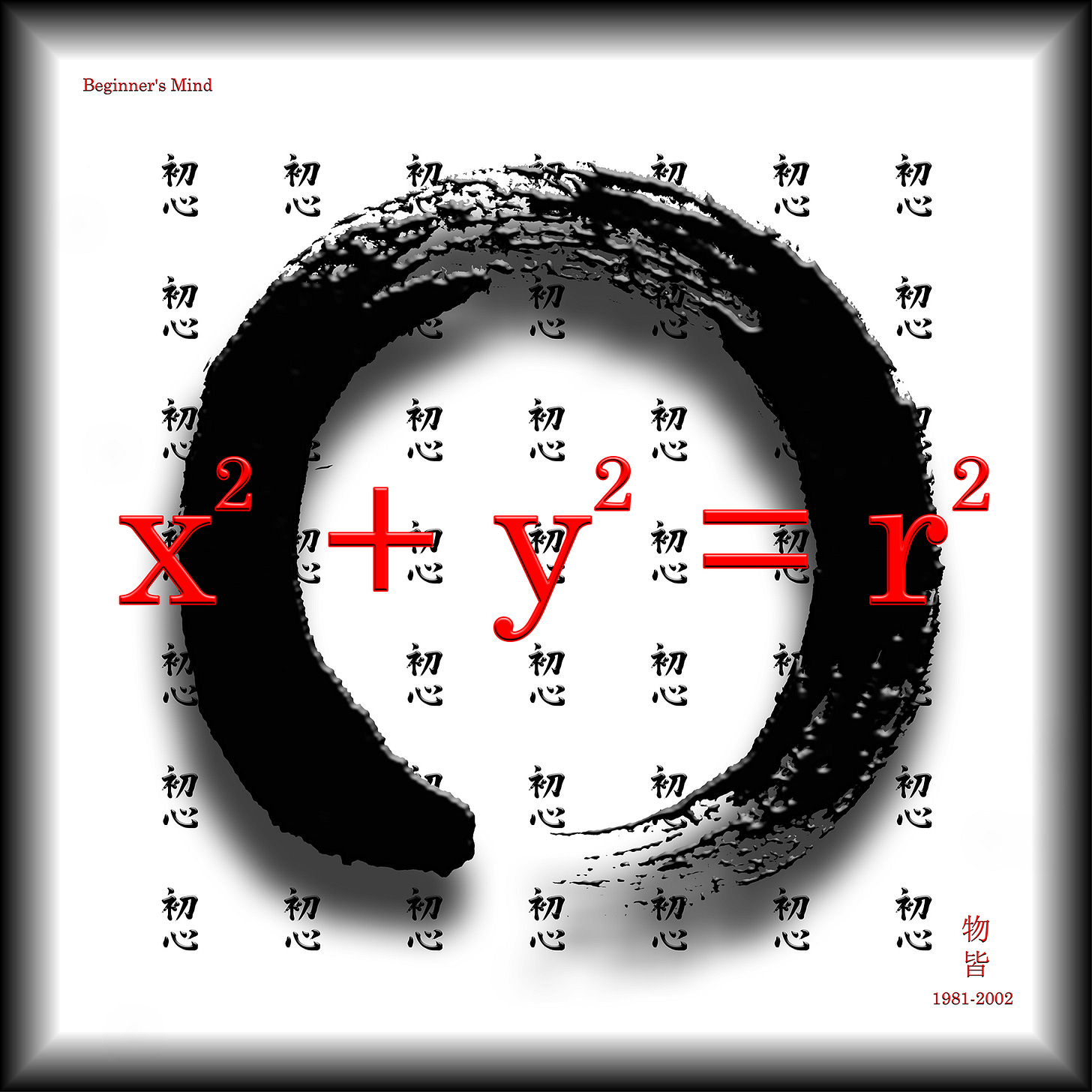

Kazmier Maslanka’s mathematical visual poem Beginner’s Mind (conceived in 1981, shared in 2002) is a meditation on this very principle—a confrontation between the rigid world of logic and the fluidity of Zen practice. At first glance, the piece appears as a grid, a carefully ordered 7x7 arrangement of the phrase “Beginner’s Mind” in Chinese script, forming a meditative backdrop. But then, layered atop this field of repetition, a dynamic interplay unfolds: a hand-drawn Zen Enzo (Il Won Sang in Korean)—a single brushstroke expressing emptiness, imperfection, and infinite potential—is overlaid with the precise, denotative equation of a mathematically perfect circle (x² + y² = r²). Though originally created in ink, Maslanka digitally integrated the Enzo into the final composition, bridging the physical spontaneity of Zen calligraphy with the calculated precision of mathematical visualization.

The Tension Between Knowing and Not-Knowing

What Maslanka has crafted here is not just a juxtaposition of East and West, nor merely a contrast of intuition and rationality. Beginner’s Mind is an act of conceptual synthesis, a space where the rigid boundaries of mathematical certainty dissolve into the flowing, non-dual awareness of Zen.

The equation is absolute—an unwavering definition of a perfect circle, its meaning rooted in Euclidean precision. The Enzo, by contrast, is a paradox: a form created by an instant of motion, where the imperfection of the human hand is part of its truth. In Zen practice, the Enzo is often drawn in a single breath, its success or failure irrelevant—only presence matters. The connotative versus the denotative, the ephemeral versus the fixed, the embodied versus the abstracted—these dialectics run through the entire composition.

The Korean artist 박 경귀 once said, “The Buddha is found at the tip of the brush.” This sentiment echoes throughout Maslanka’s work. The Enzo, drawn in a moment of pure presence, becomes a manifestation of enlightenment—not through calculation, but through action. Yet, by layering the analytic equation over this sacred gesture, Maslanka challenges us to consider whether true understanding is found in structure or spontaneity, calculation or surrender.

A Grid of Repetition, A Universe of Meaning

The 49 repetitions of “Beginner’s Mind” serve as both mantra and matrix, emphasizing the recursive nature of enlightenment. Zen practice is not about a singular moment of awakening, but rather the continuous return to a state of openness. Much like the young monk in the parable, who must empty his mind before he can receive wisdom, the viewer of Maslanka’s work is invited to let go of intellectual certainty and step into a space of experiential knowing.

Mathematical Poetry and the Search for the Absolute

Maslanka’s work has always existed at the intersection of mathematics, visual art, and linguistic play, yet Beginner’s Mind is particularly evocative in its implications. It asks us: Is perfection something measurable, or is it a state of being? Is the perfect circle the one defined by x² + y² = r², or the one drawn with a single, unbroken brushstroke? Or could it be that both—and neither—are true?

In a world increasingly driven by quantifiable logic, Maslanka’s Beginner’s Mind is a compelling reminder that true wisdom often lies in the act of unlearning. The young monk’s overflowing cup, much like the mathematical certainty of the equation, cannot contain the fullness of existence. Instead, it is in the empty spaces—the pauses between logic, the breath before the stroke—that enlightenment reveals itself.

Kazmier Maslanka’s Beginner’s Mind is not merely an artwork; it is an invitation. The only question is: Will you empty your cup?